How Surfrider Foundation chapters around the world join forces to protect our oceans.

Listen on: Apple, Google, Spotify, Stitcher, TuneIn, Overcast, Pocketcast, RSS

TRANSCRIPT

Bailey Richardson: Today Surfrider is huge. You have thousands of members and hundreds of chapters and clubs, but you started with just one small team of surfers in Malibu.

Can you tell the story of how Surfrider started and what made that group so special?

Dr. Chad Nelsen: I should start by saying, having surfers be organized around anything, it’s like the most unlikely story. Surfers really are like these lone wolfs, right? They go out surfing, they often won’t even tell their friends where they’re going. They go by themselves and then they’re in the water and everyone’s kind of fending for themselves and their secret spots. So it is a pretty unlikely group of people to be coming together for anything.

That said, Surfrider was founded in 1984 in Malibu, which is one of the most iconic surf spots of the world.

BR: Malibu is an iconic, but a very dirty surf spot. Surprisingly the water quality is bad.

DCN: And it used to be much worse!

In the early eighties, surfers were perceived as being burn outs and stoners. They were a marginalized group of people. I mean, they thought they were cool, but the rest of the world probably didn’t.

At that moment in time, surf spots were being polluted and destroyed. There’s a surf spot in a Manhattan beach, for instance, called “shit pipe” because it’s located right where the sewer pours out into the ocean.

In 1989, The Surfrider Foundation “stopped the development of a marina (an ocean entrance and a mile-long breakwater) at Bolsa Chica State Beach in Huntington Beach, California.” Photo via Surfrider

BR: I surfed there on New Year’s! [laughter]

DCN: Or Dana Point, an iconic surf spot right down the street from the Surfrider office, was destroyed by a harbor.

So we were losing surf spots and surfers weren’t organized. They were just kind of like, “this sucks. I guess we’ll move to the next spot.”

Then three guys that really together in 1984: an engineer from the Jet Propulsion Laboratory named Glenn Hening who was a surfer, Lance Carson, who was a well known pro surfer, and Tom Pratte who was an environmentalist.

Glenn was the driving force. He was inspired by the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles thinking, “Wow. Look at all these athletes standing for world peace and coming together through athleticism.” He realized surfers weren’t doing that.

As I said, Malibu Lagoon was notoriously polluted. In the middle of the summer when the lagoon would fill up, they would bulldoze it open and send all the nasty water right out into the middle of the lineup while the surfers were out there.

So Glenn, Lance and Tom said enough and they were able to effectively stop that problem in Malibu. Then they started moving up and down the coast in California fighting different problems, and the idea really caught fire.

Surfers do a paddle-out protest with Surfrider. Photo via Surfrider

I think that moment in time was a wakeup call for a lot of surfers. Surfers started realizing we don’t have to just be fatalist and accept whatever is coming at us. We can actually make a difference and control our destiny.

BR: When I lived in southern California last year, I would get in the water to surf almost every day. I realized how aware surfers are of the water quality for our health. Unless you’re in the ocean every single day like that, you just don’t think about it the same way.

I don’t know that I know any other sports where the environment you play in affects you so much, do you?

DCN: As a surfer you’re literally immersed in the water. Scuba divers are immersed too, but they don’t go in as often. Fishermen are on the top of the water. We’re actually in the water duck diving under the waves. It’s in your eyes, it’s in your ears, it’s going down your throat. You swallow water every time, whether you think you do or you don’t.

Surfers are also in the water more than any other group. There are more people going to the beach, but only half of them go in the water and they’re only doing it week a year. Surfers are on the water hundreds of days a year.

So you’re right. You’re faced with the consequences of the health of that environment. If you go running and a truck drives by, it’s nasty, but this would be like maybe running in Beijing on the smoggiest day.

The stories of people getting sick, they’re many. There are people who have died. There’s a guy in Malibu who has a pacemaker and it was from some bacteria he caught surfing at Malibu. So it’s real.

On the flip side, who better to advocate for ocean health? Surfers are the canary in the coal mine for ocean health because they’re feeling its impacts the most.

“The New Jersey Surfrider Chapter fought and won beach access for surfers at the Jersey Shore along the borough of Deal, just north of Asbury Park. This lawsuit sent a signal to other New Jersey towns not to be restrictive of surfer’s rights to access.” Photo via Surfrider

BR: What’s amazing about Surfrider is not only that you have chapters all around the world, but how tangible the impact of the advocacy and organizing is on the places we live.

How’d you develop your recipe of how to affect change like that? Had those three originators of Surfrider and studied it?

DCN: Tom Pratt, who was one of the original three, understood that to solve these problems you needed to affect political decision making. Malibu Lagoon was controlled by state parks and the water quality agency. They were the ones bulldozing the path that was sending the polluted water into the surfers.

So Tom was the guy who said, “Who’s making those decisions? How do we go impact that decision? Now let’s go organize and impact that decision,” which is Civics 101.

Mark Massara celebrating the ruling that Vinod Khosla could no longer block existing historic public access to a beach in San Mateo County, California. Surfrider’s San Mateo Chapter led the fight. Photo via the Law Offices of Mark A. Massara.

The other big organizing insight came in 1993. Nine years into Surfrider, a pretty legendary surfer and coastal attorney named Mark Massara was involved with Surfrider when we sued a pulp mill in Humboldt County, California. It was dumping their effluent out into a surf spot. The victory was the second largest Clean Water Act case in U.S. History at the time.

It was a case where the political action wasn’t working. We tried to lobby permitters to regulate what the pulp mill was doing and it didn’t work, probably because the pulp mill was powerful politically. So we sued them. It was a huge paper company and they didn’t anticipate that a bunch of surfers we’re going to have the horsepower and the knowledge to win. And we did.

That puts Surfrider on the map nationally and globally. We were featured in Life Magazine. It was in part because of the notoriety of that win but also that it was an unlikely story, right? A bunch of surfers took on this like giant paper company and won the second largest Clean Water Act lawsuit in the nation to clean up the surf spot.

Surfers are the canary in the coal mine for ocean health because they’re feeling its impacts the most.

DCN: Another guy who was really influential on Surfrider was Dr. Gordon Labedz. He was a surfer in southern California and he came out of the Sierra Club, so he believed in the grassroots model.

“In 1993, The Surfrider Foundation’s global headquarters staff in San Clemente, California, received more requests for help than they were able to process. So a chapter network was established, with the first chapters chartered in Orange County and San Diego County, California.” Photo via Surfrider

In 1993, when this pulp mill case blew up, calls came in from around the country. The organization was only three people at the time, and was like “How do we manage this national or global interest?” And Gordon was like “Chapters. Grassroots organizing. Surfers organized around their communities. They know their communities best. Let’s start the chapter model.”

BR: Three people repeating their work up and down the coast of California is very different from a team of people enabling others around the world to do that work.

What did Surfrider have to do to make that transition to chapters happen?

DCN: It happened out of necessity. Before we had chapters, headquarters would have someone call in from elsewhere and they’d just have to say, “hey, you want to solve your problem, great! Solve it. I don’t know what to tell you.”

Since the Sierra club had a model that seems to work, this chapter grassroots model, the idea was to emulate that and learn from them.

They were also naive and just made some of it up as they went along. They were like, “Hey, let’s just let go of control. We can’t control this.” And that I think is typically the hardest part. To their credit, they did let go of full control.

BR: So how has Surfrider grown since introducing chapters?

DCN: I started at Surfrider in 1998, so pretty soon after that switch to the chapter model. I think we had 20 chapters then. And today we have 200 chapters. High school clubs and college clubs have been the latest boom—we have over a hundred school clubs now.

The chapter model is genius. Locals do know best. They’re in their communities. What’s relevant on a beach in Florida is different than a remote beach in Washington State culturally, geographically and historically.

Local models help us to advocate for solutions that are practical. You can’t drop in on a parachute, tell people what they should do in their community and leave. You can’t just like throw grenades and say, “oh, you should do A, B, and C.” When you live in the community, you’re gonna see them at the supermarket the next day, so you actually have to solve real problems.

BR: Has the switch to a chapter model changed the nature of the activism Surfrider pursues?

DCN: As we’ve grown, two things have happened. One is if we work together in regions, we can scale the impact. An example would be that we were banning plastic bags in San Clemente, then in Newport Beach, and then in Monterey. We realized, “Hey, we have 20 chapters in California. If we can all work together, we can go to Sacramento and ban bags statewide,” which we did.

To do that required capacity, so now we have a woman who’s the California policy manager. She’s herding the 20 California chapter cats to get work done at the state level.

The chapter model is genius. Locals do know best…What’s relevant on a beach in Florida is different than a remote beach in Washington State culturally, geographically and historically.

The second thing that changed is we started getting proactive. We started by stopping bad projects. It was reactive. “Don’t do that condo project. Don’t felt that seawall. Don’t close that access.”

Now, instead of waiting to hear about bad things happening, we know what the problems are in advance. We ask ourselves, “How can we start to get ahead of these issues instead of just waiting for them to come to us?”

Kevin Huynh: The grassroots organizer, Marshall Ganz who worked with Cesar Chavez, has said that when it comes to organizing, people need three things: story, strategy and structure.

Hearing you speak, I hear those different elements. So from that story of getting that win up in Humboldt, the strategy was looking at who influences decisions. And then the chapter model and all of the other layers to manage the strategy, that’s the structure that helps you have an impact on a global level.

DCN: You’re spot on.

And the story is “hey, surfers are taking care of these places.” In the wildlife conservation world, they talk about charismatic megafauna. The idea is that everybody’s interested in saving the rhino, the giraffe, the elephant, and the dolphin. Nobody really cares about a random endangered squirrel or rodent species.

Surfers are a charismatic megafauna of the coastal world. People love surfing and surfers. Still to this day, they’re an unlikely hero. When we won that huge beach access case this fall up in San Mateo with Vinod Khosla, there’s no question he underestimated us because he thought we were just a bunch of surfers.

And to your structure point, we now have a “1–10-100” structure, which is one headquarters, 10 regions, 100 chapters. When we organize—like right now we’re taking on oil drilling as a federal issue—it’s not just at one level. We have our whole network, 200 chapters and clubs, working on that. Then we do things at the regional level. We have a strategy for 10 regions around the country. Then we have this network on the ground that’s local. We look for things at the local level that can scale up to the top.

The Surfrider Foundation won a huge victory when the California Coastal Commission ruled against a proposed SR-241 Toll Road extension that would have threatened San Onofre State Park and Trestles, two iconic surf beaches in Southern California. Photos via Surfrider.

KH: If today I wanted to start a new chapter, how does it work?

DCN: All of our chapters are organically born, so we haven’t placed them. A community has to come together and then we have an onboarding process. You need to organize a group of people, you need to set up an executive committee, you need to sign up a certain number of members and need to have a plan.

After the application process, then you’re on probation for six months. You need to develop campaigns and programs. If you follow all the steps through that probation time, our board charters a chapter. You get a bank account, you get our nonprofit registration, and you’re welcomed into the family.

Part of the model here is we’re all one 501(c)(3) nonprofit corporate entity and the chapters benefit from that structure. They get a lot of services—a bank account, audit and legal support. They also get organizing training, expertise, IP from our programs, branding and all of that.

In some ways it’s like a franchise model. If you’re like opening up a McDonald’s or a Starbucks, you get a similar kit. In terms of like how we structure our chapters, we look to those entities for modeling for sure.

KH: That’s really interesting. So there’s this stage of not just applying, but as you call it probation or try out or essentially making sure that chapter is solid, serious, and set up for success before they come into the fold as an official part of the organization.

DCN: Yeah. When the board charters a new chapter it becomes official.

KH: And who’s a part of that board? Is it made up of both members and sort of other chapter leaders or is that like the board of the nonprofit?

DCN: It’s your classic nonprofit board. Our board ranges between 15 and 25 people and is made up of three or four groups of people.

It’s in our bylaws that we have chapter representatives on the board so we stay true to the model. Then we tend to have some business or finance people because fundraising is always a challenge with a charity. We tend to have action sports folks and people connected to the outdoor industry on our board. And then we have some lawyers and policy experts. We really have some of the best sort of legal and policy minds on ocean and coastal issues in the country on our board and volunteering as lawyers, which we’re really fortunate to have.

Surfrider beach cleanups in action. Images via Huntington Beach’s Chapter website and Surfrider.

BR: The work of a Surfrider chapter leader is no joke. It’s a lot of effort.

People are always amazed by the willingness of community members to give so many hours to something like Surfrider when they’re not getting paid to do it.

DCN: Yeah, I still am every day.

BR: I’m sure that every chapter leader has a different reason that lead them to raise their hand and say they want to open a chapter , but what are some of your instincts around what gets a person to cross that line?

DCN: The first line people cross is they show up.

Lots of people are following us on social media. They may be are sending in their $25 membership. They’re reading the newsletter. They’re supporting Surfrider and they’re sort of engaged emotionally, but they’re doing it from like their living room. Those people, by the way, are hugely important because they help fund the work. They’re also the pool from which the activists come from.

But that moment when they show up physically is a huge deal for an organization that’s run by grassroots volunteers. That could be a movie night or some sort of social activation. It could be an informational event where we have experts speaking. It could be a beach cleanup.

We really try to make our these actions fun, meaningful and community oriented.

People who show up usually show up because they’re curious or they they want to make a difference, but the reason they stick around and then invest is that first you might show up at a beach cleanup, but then you find yourself leading the beach cleanups, then there’s a plastic bag band or some count of civic campaign and you’re going to get engaged in that. Then you’re recruiting people to that and then you’re training people and then you’re on our executive committee and you’re running the whole chapter. Right? So it’s this kind of path that people take.

And the reason they do that is because it’s fun. There’s an amazing community. The chapters that are humming is people come because they want to see their new friends, who are their friends because they’re doing this work together. They’re actually making a difference. When you show up and you see a dirty beach and you spend two hours cleaning that beach and you turn around and you look back at it and there’s a giant pile of bags and there’s a beach with no lid on it you feel a sense of satisfaction.

Surfrider San Diego Chapter member dresses on theme to speak out against single-use plastic bags, via Surfrider.

My favorite is when we’re doing something at a city council meeting because civic engagement is a huge part of this, and is frankly something we need more of in our country.

That starts with going to go to a city council meeting in your town. But it’s terrifying, right?

You go into a room designed 50 years ago to stand up at the microphone. It’s on the radio. The process is confusing. What is it on the agenda? When’s my issue? There are eight people with microphones behind a dais. They’re usually up higher than you. They have dry voices. They’re doing it every day, so half the time they’re like texting while you’re talking to them.

So we get these phone calls, “I’m going to the city council meeting. I’m freaked out. What do I do? I don’t know if I know everything. This is terrifying.” We coach them through that process and then they hopefully get 10 of their friends to show up because at a local meeting if 15 people show up you’re a mob. They get up in front of the microphone and give their testimony shaking like a leaf.

But when the city council responds, often they realize, “Oh my God, I am the expert in the room because I’ve been thinking about this so much.” Then they win and you get the phone call the next day. They are so pumped. It’s like a sporting event.

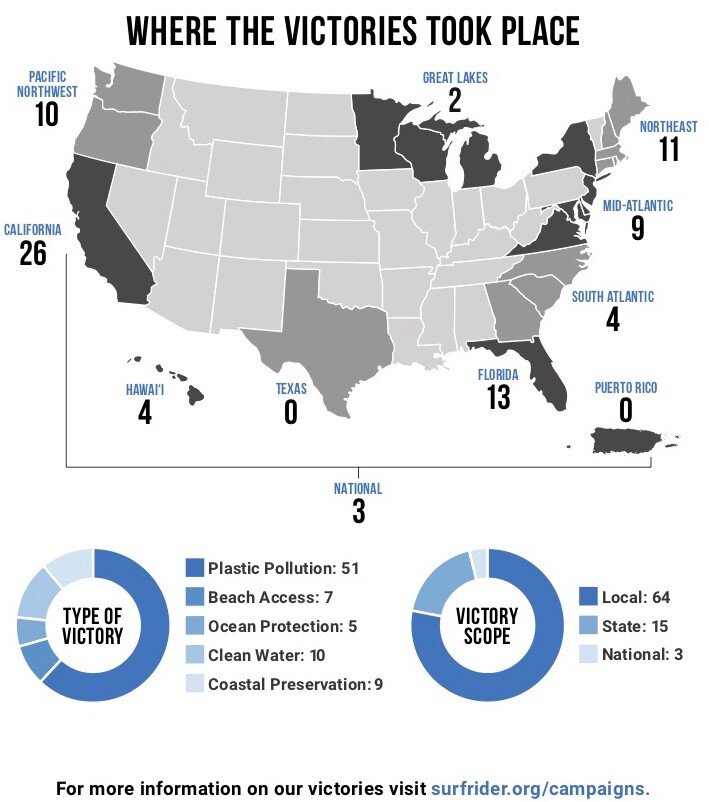

We’ve had 535 victories since 2006. Each one of those, if you think about it, is like a little sporting event that took place. There was some challenge and these group of people got in there and they campaigned, they lobbied, they recruited their friends, they had a compelling argument and they convinced this decision-making body to make the coast cleaner and healthier.

BR: You just mentioned your coastal victories.

The design of this coastal victory metric that Surfrider uses is so genius. It gives every local victory value, but also the impact the organization as a whole is having brings to life.

Can you explain what a coastal victory and how you came up with the idea?

DCN: A coastal victory for us means an official decision made in the benefit of the coastal and ocean environment or access to it. It needs to be made by an official decision making body that has legal authority. That could be a city council, that could be a regulatory body like the Corps of Engineers, it could be the state legislature or it could be the Department of Interior and the federal level.

The decision they make has to actually make a tangible difference. A beach access was opened. Plastic bags were banned. A seawall is prohibited. A marine reserve was established. Or it could be a legal victory too. We just wanted to make sure it was something that was real. If you get 50 people to show up at a public hearing but you lose the vote, the world didn’t get any better.

Why join Surfrider? You’re going to have friends for life. I hear people say this is the best thing that they’ve ever done, and that’s pretty amazing.

Beyond all the good work we’re doing, there’s that human element that’s probably equally valuable.

The design of the metric reflects the grassroots model. Today we have something like 113 active campaigns all over the United States, but they’re varied because they’re relative to what’s going on in each community. Beach access is a huge issue in Florida but it’s not a big deal in Oregon. A victory in Santa Monica could be a wetland protection case. In New Jersey it could be a balloon release ban. In San Diego, maybe it’s a sea level rise issue.

They’re not all even in terms of impact. One victory could be stopping offshore drilling across the country, a massive national campaign that took three years. Or stopping this toll road a Trestles, which took us a decade. And one could be banning smoking on the beaches in your town, which might have taken three days. But they all matter and they are all additive.

So we tried to find something that we can apply to all of these different places and all of the different issues that our chapters are working on. All of them are campaigns, meaning the chapters have decided on an outcome and they know who the decision maker is and they’re trying to compel that decision maker to an outcome.

The 2018 Surfrider Foundation “Year In Review” video highlights their coastal victories.

BR: Is the coastal victory metric meaningful to chapter leaders?

DCN: Yes. The thing it did, which I think actually was incidental, is it created a culture.

We have a monthly victory call. Our chapters call in and it’s celebratory. People share, “We got this victory! We got that one!” We see three or four victories a month.

Coastal victories created a culture of focusing on outcomes. Let’s not just throw a party or a fundraiser and tell people to avoid straws. Let’s actually like get real work done.

It also captures our progress. If you have a volunteer network, people need to be seeing results and feeling like they’re making a difference to stay engaged. If you’re like, “hey, we’re all gonna work together and like seven years, we’re going to see an outcome.” It’s really hard to compel people to stay involved.

KH: I imagine that if you achieve a plastic bag ban in one area, there’s something to learn from there in another area.

How do the different chapters share what they learn about achieving a victory?

DCN: We haven’t hit a holy grail of perfect hive mind sharing, but we do have a regional staff as part of that 1–10–100 structure who help. So there are people who are managing six or seven chapters in a region who are connecting the dots at that level.

We also do regional trainings every year. The California chapters will get together or the Pacific Northwest chapters will get together for info exchange. This year we’re actually doing a national summit to bring all of our top activists from around the country together.

And we have a intranet for our chapters. It doesn’t get used as much as I think it maybe could, but we’re looking for ways to create information, exchange and share stories as much as possible.

KH: I’d love to switch gears and ask question about sustainability. How long has Surfrider been around?

DCN: Right now it’s 30 30, 35 years this summer. That’s why we’re doing this big summit. It’s our 35th anniversary.

KH: With 35 years under your belt, what do you feel like The Surfrider Foundation does that is innovative to keep money coming in to support the important work you do?

DCN: Surfrider is built around volunteers. These volunteer grassroots chapters really are the engine that gets all the work done at Surfrider.

But we have 60 staff people and we have a budget that’s over $6 million a year. We’re a solidly mid-sized NGO. There are people running the machine at Surfrider to keep it all going so we can see those impacts. Those are our accountants, HR people, lawyers, policy experts, local and regional organizers, people who are running our programs.

I think it’s really efficient because we have thousands of volunteers, hundreds of chapters and clubs and then a small staff. It’s a pyramid.

But we need to raise that money and we are a charity and that is hard work. There’s no question about it.

I can’t tell you how many people from the private sector I’ve bumped into over my 20 years here who are like, “I’m going to raise you guys millions of dollars. It’ll be easy.” And then they come in and they realize just how hard it is because there isn’t a return on investment that’s financial. It’s not like investing in a business. No one’s gonna sell Surfrider at the end of the day and have a big windfall. The ROI is a cleaner and healthier coast.

Coastal victories created a culture of focusing on outcomes.

Let’s not just throw a party or a fundraiser and tell people to avoid straws. Let’s actually like get real work done.

That said we’ve been growing and we continue to grow. We’re not at full capacity. We have more chapters are more activists and more interest than we have the capacity to support. We have growth goals that are based on full support of the network and we’re constantly chasing that. We have 20 active lawsuits. We could probably have 30 if we had another lawyer on staff.

That’s a good problem to have. That means there are more people out there interested than we can keep up with.

BR: And based on the trajectory of our environment, I’m sure the future only holds more interest in Surfrider.

DCN: Yes. So with our fundraising we’re just trying to make sure we can give the chapters and the programs the services and support that they need.

To do that, we use the classic model of an NGO supporter. We have a membership program, which is really important. Those 50,000 members are dues paying members. It’s $25 bucks, less than your Starbucks budget for the week for most people.

BR: And what do paying members get from you guys?

DCN: We have a sliding scale. For $25, you get a sticker. For $50 bucks, you get a t-shirt. You get a newsletter.

But mostly you get the satisfaction that you’re paying your small part to support the network.

If you can’t go to these city council meetings or put in hours of time organizing, and a lot of people can’t because their lives are busy, you can send in your $25, $50, $100 bucks a year. By doing that, your supporting other members’ ability to be effective at your city council meeting.

We’ve been growing and we continue to grow…We have more chapters are more activists and more interest than we have the capacity to support.

The victory metric also was a desire to show impact to people who are financially supporting us. It’s really important to be able to show our supporters that the work is making a measurable difference so that they can feel like the dollar that they invest will result in something real.

Scott Harrison, the founder and CEO of charity: water, has done this maybe better than everyone else. When he started he formed two bank accounts that direct money. So if your $10 buys a filter, it goes directly to a family in Africa, not to the charity: water operational costs. You knew your money went there 100%.

In some ways that’s done the nonprofit world almost a disservice because everyone thinks their money should go straight to the cause. Scott did a recent podcast with Reid Hoffman’s Masters of Scale where he talked about the other bank account—the admin account. He said charity: water almost went broke at one point because there was all this money going into the filters, but nothing to run the machine. He did a nice job of saying it’s really hard to raise money for the operations because everyone wants impact without realizing that there’s human energy and capacity behind that impact.

So for us, the membership is huge. It’s a sign of our influence and it’s also a revenue generator.

And also that we’re 35 years old. We’re not middle aged yet, but we’re well established. We have a track record to show for our work too. I think people decide invest in us because of that history as.

BR: You guys have built a powerful brand over the course of the 35 years that resonates with many people.

Does that help bring in fundraising through things like partnerships?

This year, Everlane partnered with Surfrider for Black Friday. Check out what they did together here.

KH: Man, I was on Everlane for Black Friday and saw that partnership. It wasn’t just a little banner directing some proceeds to Surfrider. This was an education on plastic pollution. Full front page. It was really strong messaging that felt like it was a partnership between two organizations who truly care.

DCN: That was a huge win for us and them. It came together really well.

KH: How did you develop the Everlane partnership idea?

DCN: Everlane came to us and asked, “How much does it cost to pick up a pound of trash?” It costs us $13, and they were willing to give us $13 for every purchase on Black Friday. That way they were able to quantify the impact, which I think is important to do.

The Everlane partnership is a good example of what you mentioned about our brand’s appeal. Surfrider is sort of unique and fortunate that we have a cool brand while a lot of other NGOs that do hero’s work, whether that’s the Natural Resource Defense Council or the Sierra Club, aren’t a surf brand. It’s something that we certainly benefit from. There are a lot of businesses that want to work with us and partner with us.

I think these brands appreciate our positive nature too. We’re trying to make activism fun. It’s serious business, but that doesn’t mean we can’t be sort of celebratory and what we’re trying to accomplish.

And they like the fact that it’s authentic. It’s real people making a difference in communities. There are other groups that are more top down—that are lobbyists and lawyers and scientists and economists. We work with those groups all the time. There hugely important, but their work’s just not as visible as ours.

So we have a bunch of partnerships in the surf industry, which is actually how we first met. We have a bunch of other larger non-surf industry partnerships too, like Everlane amd REN Skincare. We do a really strict due diligence process. They’ve got to be a company that’s doing good and is minimizing their impact. We turn down more than we accept. For example, Coca Cola came to us once. We had to tell them now because they were fighting against the elimination of plastic bottles in our national parks.

KH: That’s inspiring to hear. Thinking about partnerships as not just a new sponsor of the community, but like they would become a member of the community. Do they stand for the same things that we stand for? If they don’t, it could look great on the surface but would it really ring true for the purpose of Surfrider?

DCN: People have long memories. If it’s a great partnership, like it was with Everlane, because it’s with a brand that has a lot of integrity, that’s awesome.

But if we do a really bad one, we’d hear about it. Surfrider is an organization that has a lot of credibility and integrity and we want to maintain that.

Chad went to DC in March 2019 with over 100 activists, surf industry leaders, and local elected officials from around the US to meet with federal representatives about opposing new offshore drilling and promoting clean water and healthy beaches. They scheduled over 125 meetings in 2 days. Photo via Chad’s Instagram.

BR: I didn’t realize that you have been working at Surfrider for so long.

How old were you when you first started, if you don’t mind me asking?

DCN: It was 1998 and I was 28 years old. I think there were six employees at Surfrider at the time.

I tell people if Surfrider was like a dot com or a startup, I’d be rich because it has boomed. But yeah I’ve been here for 20 years and it just keeps getting more fun. So I can’t stop

BR: Why did you join Surfider as a 28-year-old?

DCN: I’m a mailroom to CEO story. First I was a grad student intern in 1995 at Surfrider. At the time I was getting my master’s degree in Coastal Environmental Management at Duke University. I was broke and I came home. My parents live 20 minutes up the road from the Surfrider office. I lived with them and I volunteered for free at Surfrider for the summer while I did some odd jobs to make money. I loved it. I was a beach guy and a surfer my whole life. I knew I wanted to get involved in environmental issues so I was like, this is the group. It was my dream job.

I volunteered at Surfrider hoping to get a job and three years later I got an environmental program job because I have a science background. I’ve just been working my way up the ladder ever since.

BR: This will be my last question. What’s a moment that really brings to life the meaning that this being your day job has brought to you?

DCN: There’s been so many moments. Surfrider is so ingrained with who I am and what I do at this point.

One thing is that I have twin boys that are 17 and they’re amazing surfers. Watching them grow up and working for them to have a better cleaner ocean, inspires me all the time. It is sort of cliché, but it’s so true.

Secondly, the a human network of Surfrider is the richest thing. I feel so, so lucky to have that. I have friends in every coastal community around the country. These are the activists who are my heroes and now my friends. I’ve known people in communities, whether it’s Portland, Maine or Satellite Beach, Florida, for 20-25 years now. We’ve been through all of life’s dramas. I’ve watched their kids grow up. I’ve seen their parents pass away. I’ve seen them get married. And we’ve been in this fight together for the whole time.

So, yeah. Why join Surfrider? You’re going to have friends for life. I hear people say this is the best thing that they’ve ever done, and that’s pretty amazing. Beyond all the good work we’re doing, there’s that human element that’s probably equally valuable.

Get Together is produced by the team at People & Company.

We published a book and work with organizations like Nike, Porsche, Substack and Surfrider as strategy partners, bringing confidence to how they’re building communities.

Stay up to date on all things Get Together.